Squamous cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis—a rare case report

Introduction

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the renal pelvis is a rare cancer with extremely poor prognosis. Its incidence is only 0.5–1% of all urothelial cancers (1,2). In most patients’ cases, SCC of the renal pelvis is associated with long-term renal calculi. Patients are usually diagnosed at an advanced stage, which results in poor prognosis. In this paper, we present and analyze a rare case of SCC of the renal pelvis with rapid progression after adjuvant radiotherapy.

Case presentation

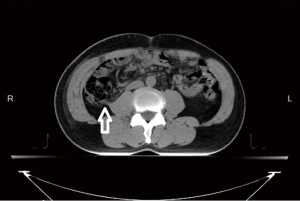

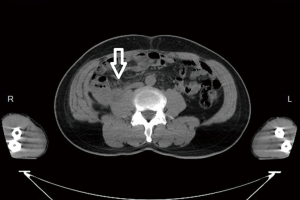

A 52-year-old male with a history of renal stone since 10 years ago had suffered from painless hematuria for a week. Physical examination of the patient showed unremarkable findings. Urine examination showed some red blood cells in urine, and biochemical analysis and complete blood count were all within normal limits. Chest X-ray showed no abnormalities. Kidney, ureter and bladder (KUB) X-ray revealed renal calculi on the right side. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen showed an enhancing mass with the size of 6.5 cm in diameter in the lower pole of right kidney. No evidence of liver metastasis or lower lung metastasis were observed (Figure 1). Clinical stage was classified as T3aN0M0 (stage III, AJCC 7th staging).

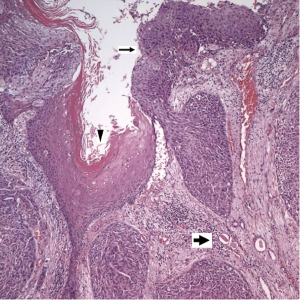

The patient underwent a right nephrectomy. On gross examination, the tumor was located on right kidney and was extended through the renal parenchyma into the perinephric fat. Histology revealed SCC, (WHO/ISUP 2004): grade III (Figure 2). Extensive sampling of the regional lymph node was performed, and microscopic examination showed metastatic carcinoma (1/1) with extracapsular spread. Surgical margin of renal pelvis had free of malignant cell. Examination of lymphovascular invasion revealed positive. Right psoas muscle also has carcinoma involved. Pathologic stage was T4N2 (stage III, AJCC 7th staging).

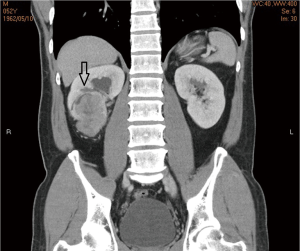

Post-operative radiotherapy (RT) to tumor bed (Figure 3) with 6,000 cGy/30 Fr was planned and performed for 6 weeks after surgery. During radiotherapy, the patient complained about intensified shoulder pain and severe fatigue; therefore, the treatment stopped at a dosage of 5,000 cGy instead of the planned dosage of 6,000 cGy. His bone scan and shoulder magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed bone metastasis at right distal clavicle. On the follow-up CT of the abdomen 4 weeks after RT, local recurrence of metastases in the right renal fossa (Figure 4), multiple metastases in the both lobes of liver, metastases in the right lower lobe of lung and bony metastases in the L2 vertebrae and bilateral ribs were noted. The patient’s condition deteriorated rapidly. Due to respiratory failure, the patient passed away within 5 months after operation.

Discussion

Primary SCC of the renal pelvis is a rare cancer. Among malignant tumors of the renal pelvis and ureter in Taiwan, the incidence of SCC is only 1% (16 among 1,494 diagnosed patients) (3).

Patients who have past history of renal calculi and have an associated poor functioning kidney or hematuria require an examination such as CT to screen malignancy recommended by Raghavendran et al. (4). A study by Narumi et al. found that renal pelvic and ureteral SCC demonstrated predominantly extraluminal extension with invasion into surrounding organs or the renal parenchyma. Narumi’s study differed from the CT appearance of the renal pelvic and ureteral transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) in a way that TCC was demonstrated as an intraluminal mass in 50% of cases (5,6). Chronic inflammation of urothelium is regarded as a cause of squamous metaplasia with subsequent malignant progression to SCC (7). The most well-known causes of chronic inflammation are long-term renal calculus disease, previous history of renal calculus surgery, chronic analgesic abuse or RT (2,7).

Symptoms such as hematuria, flank pain, flank mass and features of tumor cachexia are usually attributed to the late presentation of renal pelvic SCC (8). Most of those patients were diagnosed at advanced stage with extensive local infiltration, making surgical resection difficult (2). The lack of early-stage diagnosis could probably be explained by absent of clinical warning signs (9). Hypercalcemia secondary to pseudohypoparathyroidism has also been reported as a presenting sign (10).

In practice, patients with SCC of the renal pelvis are more likely to present with patterns of regional and distant metastasis, while TCC have a higher likelihood to present patterns at a local or in situ stage. Moreover, a recent study shows that about one third of the patients had distal metastasis at initial diagnosis (11). Due to the high risk of distal metastasis, it is critical to rule out metastatic SCC at initial diagnosis by using a combination of clinical history, imaging, and histopathology (12).

A study by Busby et al. reported that half patients have had tumor bed recurrence or distant metastasis within 5 months after operation (11). The aggressive nature of this tumor is indicated by the extensive regional spread, lymphadenopathy and metastasis to the lungs and liver but rarely to the bones. According to Hameed’s study, there were only three cases of SCC of the renal pelvis with bone metastasis reported before 2014 (8).

The outcome for patients with SCC of the renal pelvis is very poor with a median survival of only 7 months after surgery and only 7.7% of the patients survived longer than 5 years (7). Poor response to surgery, RT and chemotherapy also resulted in a poor prognosis and short survival (2).

There are still no standard treatments for SCC of the renal pelvis. Some literature suggests the primary treatment of renal pelvic SCC is nephrectomy (1,2,7,13). Surgery with nephrectomy is suggested to establish a histological diagnosis and to relieve symptoms such as pain, fever and hematuria (1,7). Cisplatinum-based adjuvant chemotherapy and RT can also be considered to improve the control of local symptoms but these treatments have failed to show any survival benefit (13).

In conclusion, our reported case showed that the patient with renal pelvic SCC had no symptoms and signs at the beginning but his condition deteriorated rapidly. Regrettably, multiple bone and liver metastases were noted after 4 months from the initial surgery. Due to aggressive nature and rapidly progression of renal pelvic SCC, close follow-up after surgery is suggested. Although uncommon, renal pelvic SCC may present with distant bony metastasis. Surgery with nephrectomy remains as the primary treatment for this type of renal pelvis. Adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy, though presents no concrete evidence of survival benefits, may still play a role for the control of local symptoms. New treatment modalities of patients with renal pelvic SCC and efforts at improving the accuracy of diagnosis at presentation are warranted.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital. I (Dr. Chia-Jung Hsu) would like to thank my colleagues from Department of Radiation Oncology who provided insight and expertise that greatly assisted the research.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: CJH serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology from May 2020 to Apr 2022. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Blacher EJ, Johnson DE, Abdul-Karim FW, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of renal pelvis. Urology 1985;25:124-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li MK, Cheung WL. Squamous cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis. J Urol 1987;138:269-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Health Promotion Administration Ministry of Health And Welfare, Taiwan, Cancer Registry Annual Report, 2014. Available online: https://www.hpa.gov.tw/Pages/Detail.aspx?nodeid=269&pid=7330

- Raghavendran M, Rastogi A, Dubey D, et al. Stones associated renal pelvic malignancies. Indian J Cancer 2003;40:108-12. [PubMed]

- Narumi Y, Sato T, Hori S, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the uroepithelium: CT evaluation. Radiology 1989;173:853-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee TY, Ko SF, Wan YL, et al. Renal squamous cell carcinoma: CT findings and clinical significance. Abdom Imaging 1998;23:203-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Holmäng S, Lele SM, Johansson SL. Squamous cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis and ureter: incidence, symptoms, treatment and outcome. J Urol 2007;178:51-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hameed ZB, Pillai SB, Hegde P, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis presenting as sacral bone metastasis. BMJ Case Rep 2014; [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berz D, Rizack T, Weitzen S, et al. Survival of patients with squamous cell malignancies of the upper urinary tract. Clin Med Insights Oncol 2012;6:11-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schaefer CJ, Geelhoed GW. Hypercalcemia in squamous cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis? Parathyroid or paraendocrine in origin. Am Surg 1986;52:560-3. [PubMed]

- Busby JE, Brown GA, Tamboli P, et al. Upper urinary tract tumors with nontransitional histology: a single-center experience. Urology 2006;67:518-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nachiappan M, Litake MM, Paravatraj VG, et al. Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Renal Pelvis, A Rare Site for a Commonly Known Malignancy. J Clin Diagn Res 2016;10:PD04-6. [PubMed]

- Singh W, Sinha RJ, Sankhwar SN, et al. Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Kidney – Rarity Redefined: Case Series with Review of Literature. J Cancer Sci Ther 2010;2:087-090.

Cite this article as: Hsu CJ, Lee HH, Shen JT, Tsai KB, Huang CJ. Squamous cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis—a rare case report. Ther Radiol Oncol 2018;2:24.